Introduction

Dislocation of the acromioclavicular (AC) joint accounts for 9-12% of all shoulder injuries(1,2), and is particularly prevalent in males (proportion 8.5:1 with respect to females)(3). The condition is most often seen in young individuals(4) in the second and third decades of life(2). The causal mechanism may be direct impact to the shoulder(5) (most often) or indirect force in relation to a fall with the hand extended(2), as typically seen in contact sports(4). Although Tossy(6) published a first classification of these injuries in 1963, the most widely used and accepted classification was developed by Rockwood in 1984. This classification describes 6 types of injuries according to the degree of displacement and its direction(7).

Conservative management classically has been considered the most appropriate strategy for Rockwood type I and II lesions(8), with surgery being indicated for types IV-VI(9). The initial management of type III lesions is more controversial(10), though the current tendency is to prescribe conservative treatment in the acute phase, in view of the good outcomes obtained, and to resort to surgery only when orthopaedic treatment fails(11,12).

Chronic lesions, defined as those with a duration of 3-6 weeks(13), accompanied by residual pain and dysfunction as a consequence of failed initial conservative management, also constitute a clear indication for surgery. With regard to the surgical treatment of these chronic injuries, and in the same way as in the acute cases, a great variety of both open and arthroscopic techniques have been described(3), though there is no agreement as to which is the best option in terms of the outcomes obtained or the associated complications. It does seem clear that there has been a transition in recent decades from non-anatomical to anatomical techniques, in an attempt to restore both vertical and horizontal stability of the AC joint.

The present study describes the open anatomical reconstruction technique with allograft used in our centre as surgical treatment for chronic CJ dislocations.

Surgical technique

The described surgical technique follows the principles established by Carofino and Mazzocca(14) for open anatomical reconstruction of the AC joint, with the modifications introduced by Kibler(15) regarding passage of the graft and its insertion - in the context of what the latter author described as the MADOK AC joint reconstruction technique.

Indications

The technique is mainly indicated for chronic lesions, defined as those with a duration of 3-6 weeks, accompanied by residual pain and/or dysfunction. In their description, Carofino and Mazzocca(14) also included high grade separation dislocations (grades IV-VI) among the indications, even when manifesting in acute form. A final indication would be those cases in which previous repair has failed. Nevertheless, it is essential to individualize the chosen treatment, ensuring that the clinical situation and physical examination of the patient prevail over the radiographic findings in making the definitive therapeutic decision.

Anaesthesia and positioning

The procedure is performed under general anaesthesia complemented by interscalene block. This affords a longer pain-free period for the patient once the effect of the anaesthesia has worn off - particularly in the first 24 hours(16). The patient is placed in a deck chair at an angle of about 60º in order to lessen the effect of gravity upon lower displacement of the scapula and to facilitate joint reduction. Positioning should be as lateral as safely possible, while keeping the medial margin of the scapula aligned with the edge of the table to allow extension of the arm. In addition, a small interscapular roller is placed to not only fix the scapula but also keep the shoulder separated from the surgical table - thus facilitating tunnelling of the clavicle. The affected upper extremity is sterilized and covered with sterile sheets, affording free access to the entire clavicle, the AC joint and the acromion.

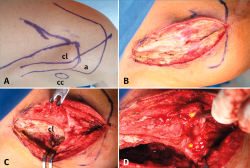

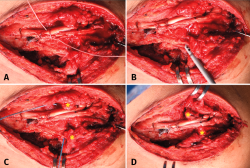

Approach and dissection (Figure 1)

The skin incision extends longitudinally from the upper zone of the middle third of the clavicle to the lateral margin of the acromion (Figure 1A).

[[{"fid":"5148","view_mode":"default","fields":{"format":"default","alignment":""},"type":"media","field_deltas":{"1":{"format":"default","alignment":""}},"link_text":null,"attributes":{"class":"media-element file-default","data-delta":"1"}}]]

Deep dissection is carried out with an electric scalpel, performing careful haemostasis, starting medially and reflecting the trapezoidal fascia with the instrument (Figure 1B and 1C). It is especially important to adequately identify and isolate this fascia and even place some sutures in it at this stage of the procedure, as they will be of help in performing adequate final repair. As dissection progresses laterally, we must identify and protect the remnants of the anterior and posterior AC ligaments, which almost always remain anchored to the acromion and can be identified under the distal clavicle, interposed between the acromial and clavicle joint surfaces (Figure 1D). These ligaments are essential for achieving adequate repair of the AC joint, and are usually identified even in individuals with lesions that have been present for years. In the next step we identify the coracoclavicular interval following the vertical line from the insertion of the conoid and trapezoid ligaments in the lower surface of the clavicle and palpating the tip of the coracoid process. A split is then made of the tissues between the clavicle and coracoid process, and we clean the lower surface of the latter in order to correctly pass the graft.

In order to achieve adequate joint reduction, it is essential to eliminate all the cicatricial tissue interposed between the clavicle and the acromion, produced over the chronic course of the lesion. In certain cases we also need to resect some marginal osteophyte that may impede reduction, but resection of the distal clavicle is not indicated, except in cases of extreme deformity of the latter, since resection could lead to a serious imbalance of the thoraco-scapulohumeral kinetics.

Once the joint has been reduced, provisional stabilization of the latter is carried out by placing a 1.5-mm Kirschner pin from the lateral margin of the acromion to the distal clavicle through the joint, and taking care not to insert the pin to the region of the clavicle where the orifices for passing of the graft are to be made.

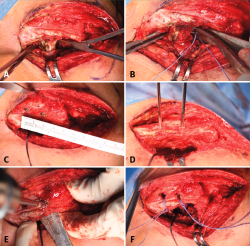

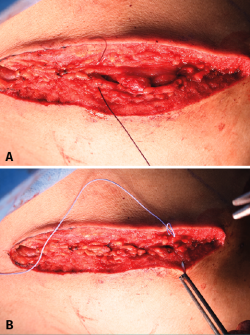

Coracoclavicular reconstruction (Figures 2 and 3)

Using a 5-mm drill, two orifices are made in the distal clavicle, corresponding to the insertions of the conoid and trapezoid ligaments. If a cannulated drill is used, two previously positioned Kirschner pins will serve as guides over which drilling is to be performed. The conoid orifice lies in a medial position about 2.5-3 cm from the distal end of the clavicle and guided from the posterosuperior marginal of the latter towards the conoid tubercle, palpable on the lower surface of the clavicle and located immediately superior to the medial margin of the coracoid process. The trapezoidal orifice in turn lies approximately 1 cm anterior and 1.5-2 cm lateral to the conoid orifice, depending on the size of the clavicle, and is directed towards the trapezoidal crest on the lower surface of the clavicle, at an angle of about 30º with respect to vertical from the lateral margin of the coracoid process (Figure 2).

[[{"fid":"5149","view_mode":"default","fields":{"format":"default","alignment":""},"type":"media","field_deltas":{"2":{"format":"default","alignment":""}},"link_text":null,"attributes":{"class":"media-element file-default","data-delta":"2"}}]]

For reconstruction we use a tendon allograft supplied by the tissue bank of our centre and measuring at least 260 mm in length and approximately 5 mm in diameter. The graft may correspond to semitendinosus, hallux or tibialis anterior or posterior muscle, adjusting the diameter if necessary. Any one of these options is adequate, provided it meets the mentioned specifications referred to length and diameter; the use of one option or other therefore depends on availability. Number 2 Vicryl® sutures placed at the extremities of the graft will be of help in passing the graft along the lower surface of the coracoid process and through the clavicular orifices. In addition to the graft, we use a high-resistance polyethylene tape (UltraTape®, Smith & Nephew, Boston, USA) folded in four to afford primary stability to the coracoclavicular fixation.

Respective Vicryl® "thread passing" sutures placed in the clavicular orifices will facilitate passage of the graft and tape through them. These sutures are inserted folded in half through the orifices, forming a loop through which the graft and tape are passed.

The passage of both beneath the coracoid process can be done in two ways: directly, inserting an angled dissector or alternatively a Crawford from medial to lateral and recovering them from lateral to medial, thereby minimizing the risk of damaging nearby neurovascular structures; or indirectly, using the dissector to pass a suture folded in half, which then will be used to pass the graft and tape.

In the technique described by Kibler(15), the graft and tape are first passed directly beneath the coracoid process, and then each extremity is inserted into the corresponding clavicular orifice with the help of the "thread passing" sutures - the loop being placed ventrally to allow passage from ventral to dorsal.

[[{"fid":"5150","view_mode":"default","fields":{"format":"default","alignment":""},"type":"media","field_deltas":{"3":{"format":"default","alignment":""}},"link_text":null,"attributes":{"class":"media-element file-default","data-delta":"3"}}]]

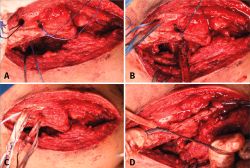

At this point the authors have modified the technique, first inserting the graft and tape through the medial clavicular orifice, with the suture loop positioned dorsal within the orifice, in order to pass them from upper to lower on applying traction to the suture extremities (Figure 3A). We then pass the graft and tape beneath the coracoid process indirectly, with the help of a "thread passing" suture (Figure 3B). Lastly, within the lateral orifice the suture loop is located ventral in order to pass the graft and tape from lower to upper (Figure 3C). The tape is then knotted over the upper surface of the clavicle (Figure 3D), the graft is tensed manually, its two extremities are tied together with interrupted sutures, leaving the distal half free, and the Kirschner pin that was placed at the start of the procedure is removed, checking that there is no loss of reduction.

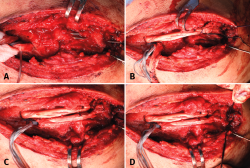

Acromioclavicular reconstruction (Figures 4 and 5)

After completing the coracoclavicular reconstruction, we must address the AC joint, reproducing the insertion of the superior, anterior and posterior AC ligaments. The extremities of the graft will be used to reconstruct the first of these ligaments. For this purpose, they are tunnelled through the lateral acromion in concordance with the modifications of the original technique described by Kibler et al.(14), thereby affording safer fixation. Using a 1.5-mm Kirschner pin, two orifices are made in the acromion from its most lateral margin to its upper surface at the medial margin, which we roughen slightly to facilitate incorporation of the extremities of the graft, which because of their diameter cannot penetrate the acromial tunnels and remain affixed at the roughened surface. The first orifice is located in the anterior third of the lateral margin of the acromion, and the second in the posterior third (Figure 4A). Respective "thread passing" sutures are used in the same way as in passing the graft and tape through the clavicular orifices. The tensed graft is positioned over the acromion to determine which length is adequate to reach the medial acromial orifices. At the determined distance, a suture is placed in each extremity of the graft. These sutures in turn are inserted through the sutures previously placed in the acromial orifices; on applying traction to the latter, the extremities of the graft are affixed to the medial surface of the acromion (Figures 4B and 4C). Then, the tunnelled sutures are knotted over its later margin, and the remnant portion of graft is sectioned (Figure 4D). This remnant portion corresponds to the distance from the original extremity of the tendon to the suture we have placed in it and tunnelled.

[[{"fid":"5151","view_mode":"default","fields":{"format":"default","alignment":""},"type":"media","field_deltas":{"4":{"format":"default","alignment":""}},"link_text":null,"attributes":{"class":"media-element file-default","data-delta":"4"}}]]

Lastly, we must repair the anterior and posterior AC ligaments. This is done by placing two 1.7-mm all-suture implants (SutureFix®, Smith & Nephew, Boston, USA) at the anterosuperior and posterosuperior margin, respectively, of the distal clavicle. They are used to fix the tissue remnants in their anatomical position (Figure 5).

[[{"fid":"5152","view_mode":"default","fields":{"format":"default","alignment":""},"type":"media","field_deltas":{"5":{"format":"default","alignment":""}},"link_text":null,"attributes":{"class":"media-element file-default","data-delta":"5"}}]]

Once reconstruction has been completed, we check stability in both the vertical and the horizontal plane.

Repair of the trapezoidal fascia and closure (Figure 6)

We then carefully repair the trapezoidal fascia with simple interrupted number 2 Vicryl® sutures and close the subcutaneous cellular tissue with interrupted number 0 Vicryl® sutures. Staples are used for closing of the skin. The procedure is completed by placing a sterile dressing.

[[{"fid":"5153","view_mode":"default","fields":{"format":"default","alignment":""},"type":"media","field_deltas":{"6":{"format":"default","alignment":""}},"link_text":null,"attributes":{"class":"media-element file-default","data-delta":"6"}}]]

Postoperative management

After surgery, the patient must wear a sling for three weeks. During this period, internal rotation and abduction is not allowed, though active scapular depression and retraction is possible in order to lessen loading through the AC joint. After these three weeks, active elevation to 90º is allowed. Active elevation beyond 90º is to be avoided until the sixth postoperative week. The patient can return to daily life activities and strength after 12-16 weeks.

[[{"fid":"5154","view_mode":"default","fields":{"format":"default","alignment":""},"type":"media","field_deltas":{"7":{"format":"default","alignment":""}},"link_text":null,"attributes":{"class":"media-element file-default","data-delta":"7"}}]]

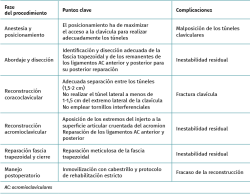

Table 1 describes the main complications that may arise and the key points for avoiding them over the course of the procedure.

Discussion

The surgical treatment of chronic AC dislocations, whether indicated due to failed previous conservative management or surgery, constitutes a challenge for the surgeon. The aim of treatment in the case of acute dislocations is to join the extremities of the ligaments to facilitate their healing. However, it has been shown that these ligaments lose their healing potential from three weeks after the initial injury(17). Therefore, in chronic cases, an additional biological adjunct to mechanical stabilization is particularly important in order to achieve better clinical-radiological and functional outcomes.

In the same way as in acute lesions, a number of surgical techniques have been developed for the treatment of chronic lesions, and these techniques in turn have experienced modifications over time. In this regard, different studies have attempted to establish the possible superiority of certain techniques over the rest.

In 1972, Weaver and Dunn(18) introduced transpositioning of the coracoacromial ligament to the distal clavicle, together with resection of the latter, for the treatment of AC dislocations. This non-anatomical technique had a number of mechanical disadvantages(3) that resulted in the development of a series of alternatives. In 2004, Sloan et al.(19) found that the lateral half of the combined tendon could be a viable and slightly more stable option than transference of the coracoacromial ligament - though a loss of reduction may be observed in the radiological evaluation in up to 21% of all cases(20). Other alternatives are the combined transference of the lateral half of the combined tendon plus the coracoacromial ligament(21) or the anatomical reconstruction with the coracoacromial ligament and the short head of the biceps(22).

The use of tendon grafts was introduced with the aim of achieving greater mechanical stability, and to afford a biological adjunct capable of incrementing the healing potential. Carofino and Mazzocca(14) published their preliminary results in 17 patients with chronic AC dislocations subjected to anatomical coracoclavicular ligament reconstruction (ACCR) using a semitendinosus allograft passed beneath the coracoid process and through respective tunnels in the clavicle, affixed with interferential screws. The AC joint was repaired, maintaining the distal clavicle. The patients experienced significant improvement in terms of pain and function. The mean ASES (American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons) score increased from 52 before surgery to 92 at the end of follow-up. The Constant-Murley score also increased from 66.6 to 94.7. There were three failures in this series, of which two required revision surgery.

Kibler et al.(15) reported the objective and functional outcomes of the surgical treatment of 15 patients with type III-V AC dislocations based on the technique presented in this article - a modification of the technique developed by Carofino and Mazzocca(14). After a mean follow-up of three years, only one patient showed a loss of reduction after a fall. The rest of the patients presented radiographic and clinical stability, with a statistically significant decrease (p < 0.0001) in coracoclavicular distance (0.93 cm on average) with respect to the preoperative distance (2.7 cm on average), and a likewise significant improvement (p < 0.0001) in the DASH (Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand) score, which decreased from an average of 51 points preoperatively to 13 at the end of follow-up.

More recently, Saccomanno et al.(23) reported good clinical-radiological outcomes using an anatomical reconstruction technique with semitendinosus autografts, in the same way as Cerciello et al.(24), employing allografts. Both approaches follow the same principles of combined coracoclavicular and AC reconstruction.

Different synthetic plasties have also been used with the aim of providing primary stability and inducing healing through fibroblast colonization(3). However, studies comparing the results of these plasties versus biological grafts(25) have evidenced the clinical superiority of the latter. On the other hand, their use has also been associated to a significant number of foreign body reactions(26), which would limit their utilization.

Different studies have attempted to determine whether certain techniques are superior to others. Borbas(27) conducted a systematic review comprising 27 studies with levels of evidence II to IV. The analysed surgical techniques were divided into non-biological fixations, biological reconstructions with auto- or allografts, and ligament and/or tendon transference procedures. In terms of the functional outcomes, the mean score of the Constant test was 87.2 points for the first type of technique (n = 89), 92.4 points for the biological reconstructions (n = 86), and 87.4 points for the ligament and/or tendon transferences (n = 49). Among the level II studies, the authors observed better functional outcomes in the tendon graft reconstruction group.

On the other hand, the systematic review published by Xará-Leite et al.(28) comprised 28 studies, with division of the techniques into two main categories: anatomical and non-anatomical reconstructions. Significant improvements were observed in the Constant score, with a mean of 11.1 points preoperatively versus 50.7 after surgery (p < 0.01). The mean failure rate was 7.6% (7.5% in the case of the anatomical reconstructions versus 8.5% for the non-anatomical reconstructions).

Sircana et al.(29), in their systematic review of 44 studies, found synthetic reconstructions to offer better functional outcomes than internal fixation and the biological techniques (p < 0.0001). Among the biological techniques, combined coracoclavicular and AC reconstruction yielded better Constant (p = 0.0270) and ASES scores (p = 0.0113), and less pain than isolated coracoclavicular reconstruction. Biological anatomical reconstruction using grafts without augmentation showed better Constant (p < 0.0001), VAS (visual analogue scale; p < 0.0001) and SSV (subjective shoulder value; p = 0.0177) scores than the techniques with augmentation. Lastly, there were no differences in the functional outcomes between the biological anatomical reconstructions using grafts without augmentation and the synthetic reconstructions.

In our centre we chose the surgical technique of Carofino and Mazzocca(14) with the modifications introduced by Kibler et al.(15), since it allows combined reconstruction that restores both vertical and horizontal stability(2). In fact, with this technique we restore the function of the superior AC ligament, which has been shown to be the most important component for rotational and posterior stability(30). In addition, whenever possible, we also repair the rest of the AC ligaments(31). On the other hand, the use of grafts affords the biological adjunct to compensate the loss of healing potential seen in patients with chronic lesions. The fact that no interferential screws are used for plasty fixation allows us to use smaller diameter tunnels in the clavicle, thus preventing perioperative fractures and potentially reducing complications related with the material. Lastly, the use of a tape allows adequate primary fixation while graft incorporation takes place.

Conclusions

The described technique constitutes a reproducible alternative for the treatment of chronic AC dislocations, combining the advantages of the biological adjunct, in the form of grafts, with anatomical reconstruction, in an attempt to restore both the coracoclavicular ligament complex and the AC.